Introduction

Media is a fundamental pillar in the construction of modern societies, given its vital role in shaping public opinion, fostering collective awareness, ensuring oversight and accountability, and delivering truth to the public with professionalism and impartiality—qualities that Syrian media has lacked for decades.[1]

In the Syrian context, the importance of ethical journalism stands out as a vital factor in strengthening public trust in the media and in ensuring that journalism serves as a tool for accountability and transparency. This importance becomes especially evident in light of the major challenges facing the Syrian media sector, including hate speech, stereotyping, and the disregard for the dignity of victims—practices entrenched by the Assad regime.[2]

Journalistic practice, in principle, is governed by a set of laws, regulations, and rules intended to organize the field. Among these are commitments to truthfulness, integrity, accuracy, and objectivity in reporting; respect for individuals’ privacy, dignity, and rights; and the avoidance of violations in any form. Yet these principles have long been marginalized under Syrian law and by authoritarian governance, which steered the media to serve its own agendas for decades.

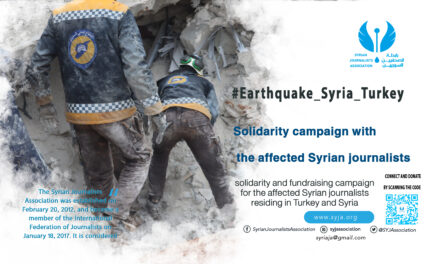

Against this backdrop, the Syrian Journalists Association (SJA) has supported journalists—both men and women—and sought to empower them to practice their profession freely and professionally. It has organized targeted training sessions and dialogue forums to highlight the importance of adhering to ethical values in journalism and their role in fostering public trust.

The SJA was founded on February 20, 2012, in response to the urgent need for a professional body to support Syrian journalists, particularly amid the challenges that emerged with the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011.

Since its establishment, the SJA has played a pioneering role in institutionalizing ethical journalism standards and in providing dialogue platforms that help entrench professional and ethical norms for journalistic practice while confronting the challenges threatening media independence. Its efforts have focused on several key areas:

- Establishing the Syrian Center for Media Freedoms to monitor and document violations committed against journalists and media institutions in Syria, as well as violations targeting Syrian journalists abroad. The association issues periodic reports highlighting these violations, thereby raising awareness of the risks journalists face and pressuring those in power to halt such abuses.[3]

- Organizing numerous training courses and workshops to strengthen members’ journalistic skills, covering diverse areas such as journalist safety and security, video reporting, and investigative journalism. These trainings have helped journalists improve professional performance and adapt to field challenges.

- Creating a training and capacity-building center to raise the professional standards of journalists, enabling them to keep pace with technological and methodological developments in the field while seeking new opportunities for education and training.

- Providing free legal advisory support for journalists subjected to violations or legal prosecutions as a result of their work, in addition to logistical and financial support in some cases, and mediating with international actors to secure recommendations and assistance for journalists in need.

- Offering multiple user-friendly services through its website, allowing journalists to report violations, request corrections to past records, and apply for identification or recommendation letters needed in their work.[4]

- Developing a code of professional conduct for Syrian journalists and working to promote professional and ethical journalism. Together with independent media organizations, the SJA launched the “Charter of Honor for Syrian Media Professionals” as a guiding framework for consolidating ethical journalism standards in Syria.[5]

- Securing membership in the International Federation of Journalists on January 18, 2017, which enhanced its international presence and enabled stronger advocacy for Syrian journalists at the global level.

Through these wide-ranging efforts, the SJA has become a genuine umbrella organization supporting Syrian journalists, defending their rights, and working to enhance their professional capacities, despite the significant challenges it has faced since its inception.

Journalism in Syria continues to grapple with profound challenges shaped by the nature of the conflict over recent years, the multiplicity of actors, and fragmented territorial control. These factors have deeply affected the media environment, the credibility of content, and professional ethics. Within this complex context, the urgent need arises for a comprehensive study of ethical journalism—not merely as a professional obligation but as a necessity to ensure responsible, independent media that respects human dignity and counters misinformation and bias.

This study aims to examine the concept of ethical journalism in the Syrian context and to explore its relationship with the laws regulating media work, which—whether directly or indirectly—shape the general media climate and define the limits of freedom and ethical standards, either by supporting or restricting them. In the absence of a unified, comprehensive media law in Syria, and given the multiplicity of legal frameworks across areas of control, the gap between existing legal texts and international ethical standards has only widened.

The study is built on a multi-layered methodological framework combining legal analysis of media laws and regulations with field analysis conducted through a broad survey of 140 journalists, in addition to three dialogue forums involving participants from various Syrian regions. The research concentrated on the evolving contexts across different geographical areas, with particular focus on conditions before the “liberation” of certain territories and the subsequent local dynamics that emerged. This approach enabled the research team to expand and tailor the survey in ways that reflect the Syrian reality and keep pace with legal and regulatory developments affecting journalism and journalists.

At its core, the study addresses a central research question:

To what extent are the laws regulating media work in Syria aligned with the principles of ethical journalism, and how can this alignment be strengthened to support a professional and independent media environment?

This question gives rise to several related issues: journalists’ awareness of ethical standards, the violations they face, the role of regulatory institutions, and the tensions between domestic laws and international norms.

The study does not stop at identifying these problems but seeks to present practical recommendations grounded in international ethical frameworks and in the perspectives of journalists themselves. Its aim is to help improve the media environment in Syria and contribute to building journalism that is more professional, free, and independent.

I. Conceptual Framework and Research Methodology

Ethical journalism plays a decisive role in fostering a professional and responsible media environment, especially in the Syrian context, where the media landscape suffers from complex challenges. These include ongoing violations of journalists’ rights, the spread of disinformation, political and regional fragmentation, and the absence of a unified legal framework that safeguards journalistic work and ensures its independence. Commitment to ethical standards in journalism enhances credibility, reduces the circulation of misleading information, and protects the dignity and rights of individuals within news coverage.

In Syria, where multiple actors shape the media landscape—ranging from state-run institutions loyal to the Syrian government, to independent or opposition-affiliated outlets, as well as media linked to various local and international forces—the need for common ethical standards becomes increasingly urgent. Ethical journalism is not limited to professional competence; it also entails avoiding hate speech, verifying sources, refraining from bias, and respecting privacy in reporting. These principles are vital in a crisis-ridden environment such as Syria.

The laws regulating media work constitute the legal framework that should protect journalists, guarantee freedom of expression, and outline the ethical boundaries of the profession. In Syria, however, these laws differ across regions: areas under government control, opposition-held territories (formerly), and those under the Autonomous Administration led by the Democratic Union Party (PYD). Each area enforces different legal systems, producing a fragmented and often hostile media environment.

Achieving alignment between media laws and ethical standards is therefore essential to guarantee a fair and independent media environment. In many cases, laws restrict rather than support journalism and are sometimes used to justify violations against journalists, whether by state or non-state actors. This research thus seeks to examine these laws and assess their compatibility with ethical principles of journalism, such as those articulated in international frameworks like the International Federation of Journalists’ Global Charter of Ethics and the Munich Declaration of the Duties and Rights of Journalists.

In the current Syrian landscape, the main challenges facing ethical journalism and media laws can be summarized as follows:

- Absence of a unified law: No comprehensive media law applies across all Syrian territories, leading to discrepancies in legal implementation depending on the authority in control.

- Censorship and violations: Journalists have faced restrictions on their freedoms, whether through repressive laws or by means of violence and intimidation.

- Weak adherence to ethical standards: Disinformation, politicization of media, and biased coverage undermine journalistic credibility.

- Lack of independent regulatory institutions: In most areas, the media environment lacks independent bodies that oversee the implementation of ethical standards.

This study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of the state of ethical journalism and the laws regulating media work in Syria by:

- Analyzing Syrian media laws and their compatibility with ethical journalism standards.

- Documenting the most pressing ethical and legal violations faced by journalists in the field.

- Proposing recommendations based on international standards to protect journalistic work and strengthen a professional media environment.

The study does not stop at documenting problems but also aims to offer practical solutions informed by international experiences and by the recommendations of Syrian journalists themselves regarding ways to improve the media landscape.

The research is based on a multi-layered methodology that combines legal analysis with field analysis, supplemented by direct surveys with journalists to ensure comprehensive evaluation.

During the preparation phase, the research team at the Syrian Journalists Association conducted a thorough review of media laws and regulations in different Syrian regions and compared them with international laws and ethical standards. The team also carried out a focused survey with 140 journalists across Syria (40% women and 60% men) to assess their knowledge and awareness of issues related to ethical journalism, the key laws regulating media work, and the challenges they face within this framework.

In addition, the team organized three dialogue forums covering different geographical areas in Syria. These forums served as methodological tools to provide space for discussions on ethical journalism and the impact of regulatory frameworks on journalists’ work.

The research draws on a range of legal and reference materials, most notably Syrian media legislation, including Law No. 108 of 2011, other related media regulations and decrees, as well as media laws and decisions applicable in northeastern Syria. Comparative laws from other countries are also considered, alongside international conventions such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Munich Declaration on Journalistic Ethics, among others.

The study adopts a definition of ethical journalism as a set of professional principles guiding journalists’ conduct, including accuracy, impartiality, independence, and respect for human rights.

Ultimately, this research represents an attempt to examine and better understand the relationship between ethical journalism and the legal frameworks regulating it in the Syrian context. It aims to provide an accurate scientific assessment of the current situation and present recommendations that may contribute to building a more professional and independent media environment. The hope is that this study will serve as a valuable reference for journalists, researchers, and policymakers seeking to improve the

II. Analysis of the General Context of Journalism in Syria

The media environment in Syria constitutes a direct reflection of the political, social, and legal changes that the country has witnessed during the past decades, and especially since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011. These transformations led to reshaping the media scene in terms of structure, actors, and available spaces.

In this section, we shed light on the general context in which Syrian journalism operates, through analyzing the professional variables related to the reality of journalistic practice, and the challenges of independence, financing, and safety, in addition to the legal variables that regulate (or restrict) media work, in the presence of multiple legal references according to areas of control, and the absence of a unified and comprehensive media law.

1: Professional Variables

Syrian journalism, since its emergence in the middle of the nineteenth century until our present time, has passed through transformations and great changes, as a result of living through different political eras starting with Ottoman rule, passing through the French Mandate, then the period of independence in the middle of the twentieth century, and then the rule of the Ba’ath in the era of Hafez and Bashar al-Assad, reaching the Syrian revolution which ended five decades of darkness and authoritarianism and repression in Syria.

During these different eras, Syrian journalism witnessed pivotal professional changes that affected the means of communication (printed, visual, audio) as a result of a set of political, social, and economic factors.

– During Ottoman rule and the French Mandate

The beginnings of the era of journalism in Syria are considered with the issuance of the first newspaper during Ottoman rule under the name Syria on 19 November 1865, which was an official weekly newspaper issued in Damascus in both Arabic and Turkish, and it continued until the defeat of the Ottomans in the First World War in 1917.

The first official newspaper in Aleppo was issued under the name Furat in 1867, and both newspapers (Syria and Furat) were issued by orders of the governors at that time, therefore they were specialized in publishing news of the Sultanate and the orders and announcements issued by it. (History of Syrian Journalism, Shams al-Din al-Rifa‘i, 1969).

As for private newspapers, the thinker Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi established the first private newspaper under the name Al-Shahba, which was quickly stopped. Afterwards, many newspapers were issued, some of them loyal to the Sultanate, and some of them blowing early the trumpet of nationalism. The Sublime Porte thus issued decrees to regulate journalism that limited its freedom and placed every violator under penalty and suspension. The journalistic text in the Ottoman period was dominated by a religious and poetic character, rhetorical ornaments, sometimes mixed with common Turkish words, and lacking the principles and rules of journalistic writing.[6]

The beginnings of the twentieth century witnessed a real revolution in the world of journalism, where dozens of new newspapers appeared. Among the most important was the issuance of a women’s newspaper concerned with women’s rights in the Middle East, called Al-‘Arus (The Bride), in 1910 by Mary Ajami, a Syrian poet and journalist.

In 1920, the number of printed periodicals reached 31 magazines and 24 newspapers published throughout Syria. [7]After that, a new era of repression began with the start of the French Mandate in Syria, where the French authorities worked to suspend national newspapers and punish them, and to encourage loyal newspapers that supported the French presence, especially after the Great Syrian Revolt which broke out in 1925. The Press Law was issued, which limited press freedom by legal texts that imposed conditions for issuing newspapers and defined violations committed by them.

Among the newspapers issued in that period were: Al-Anwar, Sada Suriyya, Alif Ba’, Fata al-Sharq, Halab, Al-‘Asima, and dozens of others that suffered restrictions, closures, or unfair financial fines that led them not to appear again.

After Independence

With the beginning of the era of independence in Syria in 1946, journalism was organized, laws for media were issued, a code of honor was established, and rules were defined for violations and penalties in case of committing publication crimes. The same applied to radio, which was launched on the day of independence from Damascus.

During this short period of civilian rule (1946–1949), journalism experienced wide spread and prosperity by enjoying a large margin of freedom. Its topics diversified, and many newspapers and magazines were issued. This period is considered the golden stage of Syrian journalism, before the beginning of the stage of military coups, in which dozens of newspapers were abolished, strict censorship was imposed on newspapers, and Syrian journalism in 1954 breathed some of the air of freedom for a very short time, during which dozens of newspapers were issued, which were quickly closed during the era of the Syrian-Egyptian union (1958–1961).

During Ba’ath Rule and Hafez al-Assad

In 1963, the Ba’ath Party seized power in Syria, and a new stage of suppression of freedoms began. The state of emergency was declared, and laws were issued under which newspapers, magazines, and publishing houses were closed, printing presses confiscated, and journalists banned from working, so that authoritarian media was formed in its clearest form, through its subordination to the ruling party. Its first mission was to promote the goals of the party which tightened its grip on the media and adopted the policy of silencing and controlling everything published.

With the coming of Hafez al-Assad to power in 1970, the media was entrenched as one of the tools of his control over the country, through issuing laws and establishing institutions whose mission was to suffocate media freedom, entrench loyalty to the ruling party, and monitor everything related to media work and its stages (preparation, printing, publishing, and distribution).

Media in the era of Assad the father became a mouthpiece for the authority. In 1974 the newspaper Tishreen appeared, which became “the third pillar” in consolidating regime journalism alongside Al-Ba’th and Al-Thawra.[8]

Hafez al-Assad also tightened his grip on other media outlets (television, radio). His security services practiced all kinds of violations against the media (persecution and restriction of journalists, closing of media institutions) on a wider scale than in previous eras. This pushed major Syrian journalists and writers to emigrate abroad. Foreign media institutions were also prevented from working freely in the country except according to Assad’s agendas and limitations.

Media in the era of Hafez al-Assad can be described as media owned by a totalitarian authoritarian power, which should only see through its eyes, and which has no tolerance for the other. Its mission was to cheer for its achievements, and to close its eyes to its mistakes, repression, and crimes. (Omar Idlibi, Harmoon Center for Contemporary Studies).

During Bashar al-Assad’s Rule

With Bashar al-Assad taking power after the death of his father in 2000, the scene did not change much, despite the “formal openness” that occurred in the beginning of his rule, represented in granting licenses to private media outlets, before matters returned to more repression in later years, especially after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011.

● Before the Syrian Revolution

The period of Bashar al-Assad’s rule between 2000 and 2011 witnessed multiple professional changes at the beginning, as he tightened his grip on the media through issuing laws to regulate media outwardly, but in reality they restricted media freedoms, imposed penalties on journalism, and prevented ownership of media outlets, among other arbitrary measures.

However, this period witnessed an opening that can be described as “formal” concerning media and journalism, as licenses were allowed for private media outlets, most of them non-political, and owned by figures close to the regime. They were under strict supervision by security services, and some of them continued until the fall of Assad’s regime, while others were closed due to crossing red lines, such as (Al-Domari).

In the end, Bashar al-Assad continued on his father’s path in controlling the media, repressing freedoms, monitoring, and employing everything published to praise the authority and the ruling party. Matters continued in this way until the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, which began another stage that reached the peak in practices of repression and violations against media in Syria, which has ranked at the bottom of the global press freedom index for years.[9]

Professional Variables of Journalism after 2011

With the outbreak of the Syrian revolution at the beginning of 2011, “alternative media” appeared, which allowed journalists and citizen journalists to publish news and opinions without being subject to official censorship.

The Assad regime found itself facing a difficult media mission to confront the revolutionary movement, so it worked on tightening control and restrictions on media outlets, and on spreading counter-propaganda against opposition media that began to appear to refute its propaganda and convey events. Its media sought to hide and fabricate facts to demonize and suppress the revolution, and to minimize what was happening by promoting the idea of a “global foreign conspiracy” against Syria.

Assad’s media merged completely with the authority through its direct subordination to the Presidential Palace. Media concepts such as “freedom of expression, opinion, professional capacities, authority, accountability, and dialogue” became canceled words in the dictionary of life and practice inside Syria. Assad’s media took the role of broadcasting absurdities that occur under the rule of Big Brother according to George Orwell’s novel (1984): “What comes from instructions is executed literally only.”[10]

The Assad regime went further in committing violations against workers in the media field who opposed him and who took on the responsibility of defending the popular movement and conveying the truth of what was happening on the ground to global public opinion, whether by pursuing them, arresting them, forcibly disappearing them, killing them, or practicing all other types of violations against them.

Since the beginning of the Syrian revolution, alternative media outlets began to appear (printed, visual, audio, and electronic), in addition to the establishment of media institutions aiming to organize media work, so that these outlets and institutions represented parallel media to the official regime media.

The Syrian Journalists Association was one of the first institutions to be established (February 2012) to organize media work, with currently more than 700 members inside and outside Syria.[11]

The Association, after its establishment, worked on forming a Committee for Media Freedoms to document violations committed by different parties against media. Later, the Syrian Center for Media Freedoms was established, affiliated with the Association, which continued the work of the Committee and is still continuing. It has documented in its records 1,546 violations committed against media and journalists inside Syria and abroad against Syrian journalists, from March 2011 until the end of 2024, among the most prominent of which was the killing of 478 journalists, including 327 cases at the hands of the Assad regime.[12]

Journalists were at the forefront of those who paid heavy prices to convey the suffering of Syrians to the world. They documented crimes and violations despite the threats and dangers surrounding them throughout the years of conflict.

Since the outbreak of the revolutionary movement, Syrian journalists played a pivotal role in breaking Assad’s monopoly on information. They faced campaigns of repression, pursuit, arrest, torture, and even physical liquidation. The targeting they were subjected to was not individual but systematic by the regime and other parties that tried to silence the free voice and prevent conveying the true facts to the world. The struggle of Syrian journalists against repression was an inseparable part of the Syrians’ struggle for their freedom. They paid with their lives, their freedom, and their personal stability as a price for that.[13]

In the oppressive circumstances and violence practiced against journalists in Syria during the years of the revolution, many professional variables emerged that affected ethical journalism, the most important of which were:

- Security challenges: Journalists were exposed to great dangers, from arrest and torture to killing or enforced disappearance. This forced them to make decisive decisions about whether to address certain topics or risk their lives to obtain information. According to the analysis of the survey results conducted by the Association team and which included 140 journalists across Syria, 62.9% of participants considered it necessary to find solutions to address security challenges through intensifying training and providing safety means.

- The emergence of citizen journalism and alternative media: With the outbreak of the revolution, alternative media outlets and the phenomenon of the citizen journalist appeared, which contributed to conveying the truth of what was happening on the ground and refuting the regime’s narratives.

- Differences in loyalties: The actors on the Syrian ground multiplied after the outbreak of the revolution (Assad regime, opposition, Autonomous Administration, armed groups…), which affected the credibility of media outlets due to their commitment to the political discourse of the different parties.

- Spread of disinformation and false news: With the increasing reliance on the Internet and social media as media tools, misleading and false information spread. Media workers faced a major challenge in verifying the truth of the news being published, which increased their ethical responsibility. The answers of 70.7% of participants in the survey showed that the most prominent characteristic around which other problems suffered by the sector of journalism and ethical journalism in Syria revolve is the spread of disinformation.

- Humanitarian coverage and violence: With the increase of violence, humanitarian coverage was extremely important. Journalists were forced to balance covering the atrocities of war with maintaining respect for the dignity of victims and their families, and to face challenges related to the media portrayal of victims without causing incitement to violence or insult.

Based on the answers of participants in the survey, the role of journalism in Syria was not as required. The largest proportion of answers indicated that its role was medium regarding conveying information, social awareness, and defending human rights, and weak regarding combating corruption, enhancing democracy, freedom of opinion and expression, and combating discrimination.

- The impact of social media: Platforms such as Twitter and Facebook became a main tool to convey events. But these means often lacked basic journalistic principles such as verification and documentation. Therefore, journalists faced a challenge to ensure that what was published complied with the rules and principles of ethical journalism.

Other professional, economic, and legal variables also emerged, some related to financing and its impact on journalists themselves and on the independence of media outlets. Survey participants pointed to challenges resulting from these variables (lack of expertise, differences in media laws in different areas, lack of financing…).

Many studies, research, and opinion polls conducted in different areas of control distribution indicate that today in Syria there is a clear confusion between hate speech and freedom of expression, due to the absence of frameworks regulating hate speech in Syrian laws and the absence of Arab references. State television was in the lead among the promoters of hate speech, along with the newspaper Tishreen in the era of the Assad regime. It is considered the most frequent user of hate expressions, while radios were the least promoter of hate speech. (Syrian Center for Studies and Public Opinion Research, Muhammad Khair al-Wazir – 2023).

On the other hand, opinion polls indicate that Syrian “alternative” media raised the level of professional journalistic work compared to what it was before 2011, but this new experience, according to surveys, is still weak, as alternative media has not broken the stereotypical image in society, nor succeeded in confronting hate speech, and still contains professional and ethical violations in its various media coverages.[14]

2: Legal Variables

The legal framework regulating media work in Syria witnessed successive and complicated transformations, which reflected the political and legislative changes that occurred in the structure of the state over decades, and the varying degrees of openness or closure towards freedom of expression and media practices. These transformations included successive media laws, and extended to other laws of penal nature, such as the General Penal Code and the Law on Combating Cybercrimes, which were reused and adapted to restrict media practices and peaceful activities.

In Syria, the legal system was used in many of its stages to limit press freedom, through broad and vague legal texts not compatible with international standards, which granted the authorities wide margins in interpretation and application. Reports issued by the Syrian Center for Media Freedoms in the Syrian Journalists Association between 2012 and 2024 confirmed the continued use of penal laws and administrative orders as means to pressure journalists and media institutions and punish them.[15]

In the context of the research, it is first necessary to distinguish between the professional principles in ethical journalism and the legal principles regulating media work, since every media institution must adhere to the professional principles in its work to achieve independent ethical journalism.

The Charter of Honor for Syrian Media Professionals specified in its Code of Professional Conduct the professional principles for media institutions. These principles are derived from international standards and laws related to media work, namely: accuracy, truthfulness, and clarity; integrity; respect for privacy; respect for intellectual rights; protection of sources; avoiding slander, insult, and contempt; non-discrimination; respect for the dignity of victims; not encouraging violence or incitement to crime or violation of the law; avoiding stereotyping; not fabricating and avoiding bias; responsibility towards children; avoiding harm and causing damage; and freedom of expression.[16]

As for the legal principles, they represent the set of laws regulating journalistic work and the legal rules that frame media work, such as media laws, internal regulations, executive instructions, decisions issued by the Ministry of Information or official bodies, and other related laws.

Since its beginning about a century and a half ago, Syrian journalism has been subject to the laws issued by the ruling authorities in different periods, and it was framed journalism, no more than a tool in the hands of authority, except for short periods in which Syrian journalism witnessed remarkable prosperity.

During the era of Ottoman Sultan Abd al-Aziz (1861–1876), who was inclined at the beginning towards adopting press freedom, the Press Law was issued in August 1865, and the establishment of a Bureau for the Press to monitor the implementation of the law was announced. But the law proved its ineffectiveness in stopping the movement of revolutionary publications and attacks on those in authority. Therefore, the government, in order to maintain public order in the Syrian provinces belonging to the Ottoman state, decided to take all possible measures through administrative means, regardless of the issued laws, to limit the activity of newspapers that neglected and disregarded the essential values and basic principles that are among the most important elements of national journalism.

The administrative system stopped the weak Press Law with its relatively simple freedom and opened the door to authoritarian methods. Three steps were applied to the press: warning, then suspension, then persecution of unwanted newspapers. This situation continued until the First World War in 1914. This law remained until the issuance of the new law in 1909, which came to abolish it correctly. (Shams al-Din al-Rifa‘i, 1969).

During the French Mandate (1920–1946), the main feature of the media legislation applied was repression and the issuance of successive decisions to suspend newspapers and confiscate them because of their continuous incitement to struggle to end the French Mandate.

Syria, after independence, witnessed a state of prosperity in the field of press freedoms, and dozens of newspapers and magazines were issued. The Press Law No. 24 of 1946 was issued, which was replaced in 1949 by Law No. 53 under the same title with specific changes and amendments. A number of laws and decisions were also issued to regulate the activities of printing presses and private periodicals.

The first Ministry of Information in Syria’s history was established in 1961. Before that, Syrian journalism and media outlets were under the supervision of the Ministry of National Guidance or by specialized departments at the Council of Ministers and the President of the Republic.

After the Ba’ath Party came to power in 1963, government and party leadership’s interest in media increased. As a result of this interest, a number of decrees were issued at the legal level regarding the establishment of large press institutions, such as the Al-Wahda Organization for Printing and Publishing, the Arab Advertising Organization, and the Syrian Arab News Agency “SANA”. In the same year, Legislative Decree No. 4 was issued, stipulating the closure of all private Syrian newspapers, the confiscation of printing presses, and the closure of publishing houses; thereby suspending the work of Law No. 53 of 1949 which regulated periodical publications.[17]

In the same year, Legislative Decree No. 154 was issued, which banned a large number of journalists from media work. Thus, the Ba’ath Party tightened its grip on Syrian media, adopting the policy of silencing voices and controlling everything written and said in the media.

After Hafez al-Assad came to power, Legislative Decree No. 34 of 1975 was issued, by which a censorship system for publications[18] was established under the name of the General Organization for the Distribution of Publications. According to Republican Decree No. 24 of the same year, this organization was given the authority to monitor all domestic and foreign publications and supervise their distribution. This organization was an iron hand that suffocated media freedom.

In 1990, Law No. 1 was issued, the Law of the Journalists’ Union, which stipulated loyalty to the Ba’ath Party and punished any member who deviated from the objectives of this Union.[19]

With the arrival of Bashar al-Assad to power, a new development occurred: the issuance of the General Press Law, No. 50 of 2001, granting broad powers to the Prime Minister and the Minister of Information to reject or accept licenses for new newspapers.[20]

In 2008, Legislative Decree No. 15 was issued, establishing the General Printing Organization, and this decree made all government newspapers printed in this organization by law.

During the years of the Syrian revolution, Syrian media outlets and media workers were subject to laws and legislations in different areas of control on the Syrian scene. Referring to the legal references that frame the professional and ethical standards of media content in the context of freedom of opinion and expression appears very complicated, especially with the multiplicity of Syrian geography divided, and thus the multiplicity of legal references of the de facto controlling forces on the ground which necessarily control what they want to bring out to the public according to their agendas.

Today, with the liberation of Syria from Assad’s rule, there are main laws framing media work in its different fields, namely Media Law No. 108 of 2011[21], Cybercrime Law No. 20 of 2022, texts in the General Penal Code, and other laws mentioned previously.

In the areas of North and East Syria, the Autonomous Administration established the Union of Free Media[22], and in 2015 announced the first Media Law, composed of 33 legal articles regulating media work inside its areas of control, until a new Media Law was adopted in all of Northeastern Syria in 2021, followed by the issuance of an executive bylaw for the law supervised by the Media Department.

In Northwestern Syria, there was no law regulating media work, although the margin of freedom was greater according to opinion polls and personal interviews conducted by the research preparation team. In 2023, the first draft of a Media Law in Northwestern Syria was issued, worked on by many civil society organizations and independent Syrian media institutions. The Stabilization Support Unit organized legal and dialogue sessions in several areas of Northwestern Syria and in Gaziantep, Turkey, with the aim of reaching a draft Media Law for the future Syria, which would contribute to organizing media work and preserving its freedom.[23]

The Syrian Salvation Government, which was active in Northwestern Syria, also created the General Directorate of Media. In January 2023, the “Salvation” announced the first Ministry of Information in the government, with the aim of organizing the media sector and media work.[24]

It can be said that the authorities of the Assad regime ideologized legal legislations regarding freedom of opinion, expression, and journalistic work, according to agendas that serve its interests. This was evident in the issuance of the Law on Combating Cybercrimes, as its most prominent articles criminalized and included acts that restrict and narrow freedom of opinion and expression, because they are crimes defined in vague and imprecise terms, not specified by clear criteria or definitions or clear pillars of crime, whether mentioned in the new Law No. 20 or in the General Penal Code and its amendments.

The regime put in place many laws in line with repressing any movement or criticism against it. The Cybercrime Law aims at further repression of freedom of opinion and expression, especially with the increasing popular movement and criticism of the government. A report issued by the Syrian Network for Human Rights in August 2023 [25] indicated that the regime authorities committed 146 cases of arbitrary arrest and cases of killing under torture on the basis of Law No. 20 from its issuance until August 2023.

In the same context, Articles 285, 286, and 287 of the Syrian Penal Code provide for imprisonment for anyone who publishes false information or incites racial tensions, but they link that to the condition of undermining the prestige of the state at one time or weakening the morale of the nation at another, without precise definition of what false news is, or what racial tensions are, or even what weakening of national sentiment means. Thus, the door is left wide open for the authorities to repress freedom of opinion, expression, and information whenever it wishes.

The margin of freedom granted to media work and freedom of expression and opinion differs in the areas of Northeastern and Northwestern Syria. Most studies in this regard indicate the diversity and large number of media outlets active in both regions compared to areas under regime control, in addition to the adoption of editorial policies mostly available on their official platforms, indicating adherence to ethical journalism standards, though differing in framing these standards according to donors’ agendas at times, or according to the ideologization of the de facto authorities at other times. (Analysis of Hate Speech: Hate Speech, Stereotyping, and Disinformation in the Context of Syrian Media, Muhammad al-Sattouf, 2024).

This is the case in the Media Law issued by the Autonomous Administration, which was followed by administrative decisions restricting media work freely and limiting it. The law, after its adoption, raised reservations from media bodies and workers in the field in the region, due to the lack of independence of the Media Department in the Autonomous Administration, and the existence of articles that restrict media freedoms, such as withdrawing the license from media institutions, as well as articles that authorize the judiciary to demand from journalists disclosure of their sources, in addition to disciplinary and financial penalties imposed for violations.[26] This was also denounced by Reporters Without Borders, which condemned the strengthening of procedures aiming at the authorities in North and East Syria controlling the media sector in the region, where restrictions imposed on journalists during their work are expanding.[27]

In Northwestern Syria, the situation seems different compared to other areas of influence. The margin of media practices seems broader on the one hand, but on the other hand legal and professional controls framing these practices are absent, which gave the controlling authorities in the region space to ideologize media practices according to their agendas, thereby restricting media freedoms.

The research preparation team, after the liberation of Syria, examined the media laws in force today in Syria, most notably the laws of the former regime regulating and related to media work, the Media Law currently in force in areas of the Autonomous Administration in Northeastern Syria, and the decisions issued by the Autonomous Administration in this regard.

A. Media Law No. 108 of 2011

The Media Law issued by Legislative Decree No. 108 of 2011 is considered the legal framework regulating media work in Syria. It consists of eight chapters distributed over one hundred and six articles, in addition to the issuance of executive instructions considered as detailed interpretative texts of its provisions. And although this law came after repeated demands for reforming the media system and expanding the margins of freedom of expression, a deep analytical reading of its articles reveals a legal structure that maintains the essence of authoritarian domination and the restriction of media freedoms under the cover of guaranteeing the “public interest” and the “stability and security of the country.”

The law mentioned at its outset definitions of media terminology, information, media content, media outlet, site register, traffic data, and others. What is notable in it is what the law included in defining the journalist as: “anyone whose profession is authoring, preparing, editing, or analyzing media content, or collecting the necessary information for that for the purpose of publishing in a media outlet.” This definition appears outwardly comprehensive but hides in its content what may negatively reflect on the freedom of practicing media work, since it leaves the door open before the executive authorities to restrict those who do not work within the licensed institutional framework, which makes independent journalists or those working in unregistered media outlets subject to criminalization, exclusion, or security pursuits. This necessitates a comprehensive review of the terms in the law.

The law affirmed in its Article 2 the principle of independence of media and freedom of its practice, as it stated: “Freedom of the media shall not be restricted except in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution and the law.” However, this text, despite its importance, loses its effectiveness when later restricted by a set of exceptions that grant the executive authority quasi-absolute power in evaluating media content and controlling it according to what it deems appropriate, which empties the text of its practical content.

According to the law, the practice of media work is built on a number of basic rules derived from the Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the international agreements ratified by the Syrian state. However, adherence to these standards remained merely formal. The law soon referred media practice to a narrow framework conditioned by broad concepts open to wide interpretation by the authorities, and obliged media outlets to respect them, which creates a space for arbitrary accountability, especially in the absence of a truly independent judiciary during the era of the former regime.

Law 108 obligated media outlets to adhere to the contents of the Press Code of Honor issued by the Syrian Journalists’ Union, which keeps media practice under the guardianship of an institution that was closely linked to the political and security authority[28]. This contradicts the principle of self-regulation of the profession, compared to what is practiced in advanced countries in the field of media freedoms.

It is true that the law granted journalists a set of privileges, such as not being subject to prior censorship, not being forced to disclose their sources of information except by judicial order and in a closed session, and the right to seek and obtain information “of any kind and from any source,” and to publish it after verifying its accuracy. However, these privileges, despite their importance, remained in a theoretical framework and could not be practiced freely. The law restricted them by granting the Council of Ministers the authority to issue decisions specifying the types of information that public entities are allowed to withhold, which practically means that the executive authority is the one that decides what should be known and what should not. This contradicts the principle of transparency and restricts the ability of the media to perform its oversight role expected of it in shedding light on problems.[29]

And in case a journalist requests from any public entity to obtain information, the law placed the journalist in a complicated path. On the one hand, it allowed journalists to request obtaining information, but on the other hand it granted public entities absolute comfort in this matter, since their non-response to journalists’ requests is considered a refusal. The law stated that public entities are obligated to respond to journalists’ requests to obtain information within seven days; otherwise, the non-response is considered an implicit refusal. In case of refusal, the journalist is allowed to resort to the Administrative Judiciary Court to challenge the refusal of public entities to provide journalists with information, provided that the court decides on the request within one month from the date of its submission. However, these mechanisms and procedures, even if they appear to be legal guarantees, are in reality lengthy procedures that cause the information to lose its news value, and place the journalist in legal mazes requiring complicated legal, financial, and temporal resources. Not to mention that the administrative judiciary itself often operates according to what public institutions see. This makes the promised legal protection practically useless, and therefore it has become important to note the need to amend these procedures and mechanisms in a way that allows practicing media work freely.

Perhaps the most dangerous content in the law is the list of prohibitions which media outlets are banned from publishing materials related to them, including publishing any content that might harm “national unity,” or “national security,” and everything considered an “offense to the symbols of the state.”

This list shows the size of restrictions imposed on freedom of expression and media practice, not only in terms of the wide scope of prohibitions, but also in terms of the nature of the terms used such as “national unity,” “national security,” “symbols of the state.” These are vague and elastic terms not accurately defined in Syrian laws. Their interpretation and application are left to the executive authorities, specifically the security agencies during the era of the former regime. These terms, during past decades, constituted an effective tool for silencing voices and repressing journalists. They were used to prosecute any investigation or report revealing the corruption of an official or negligence in a government institution, by considering it as harming security or defaming the symbols of the state. This was documented by reports of the Journalists’ Association, through the arrest of journalists based on media reports that exposed corruption of Assad regime officials since 2011.[30]

In a similar context of veiled legal domination, the law stated that “the provisions of the Penal Code and the laws in force shall apply to every crime not specifically addressed in this law.” This constitutes an open referral to a highly complex legal system, including exceptional laws such as the Anti-Terrorism Law, which was previously used to criminalize journalists and prosecute them before exceptional courts that lack the minimum conditions of fair trials. This represents a serious violation of the principle of proportionality between act and punishment, and undermines the concept and mission of media work. Thus, the executive authorities left the door wide open to punish any journalist who dared to work outside the agendas of the former regime authorities.[31]

Although the law created the National Media Council and defined its duties, powers, and objectives in Chapter IV, and granted it legal personality and financial and administrative independence, this personality and independence are nothing more than a formal, shapeless body. From the manner of its appointment and the linking of its core decisions to the Council of Ministers, to the powers granted to it, the legal texts in the same chapter undermined this personality and independence. This turned it into an executive tool in the hands of the executive authorities, and emptied it of its meaning as an independent regulatory body, contrary to international standards of independence for media regulatory bodies (Broadcasting, Voice, and Accountability, 2008).

An example of this is Article 22 of the law, which granted the Supreme Council for Media wide powers, including “drawing all matters related to media policies,” “establishing the bases and controls necessary for organizing the media sector,” “issuing necessary regulatory decisions and regulations,” as well as “setting the conditions related to granting licenses for media outlets.” However, these powers were undermined by subsequent approvals of the Council’s decisions which must be ratified by the Council of Ministers. Thus, these powers became only formal, since the independence of a council whose executive and decisive decisions are tied to the approval of the executive authority itself cannot be valid. This makes the council merely a tool to reproduce government directions in a regulatory guise.

The law did not stop at entrenching this approach, but went further when it exceeded the powers of the judiciary, in the text regarding the powers of the council to suspend publishing or broadcasting or cancel licenses of media outlets, stating: “In all cases where this law allows a ruling to suspend the media outlet from publishing or broadcasting or to cancel the license, the competent judiciary, based on the request of the council, shall issue a decision with immediate enforcement to suspend publishing or broadcasting temporarily until the issuance of the final judgment.” This clearly reflects the authorities’ tendency, by granting the council the power to request temporary suspension even before a final judgment, which threatens to suspend the activity of media outlets through quick administrative decisions under a legal judicial cover.

Regarding granting licenses to media outlets, although the law granted this power to the National Media Council, it stated in Article 37, paragraph (d), that the license in question does not become effective until it is ratified by the Council of Ministers. As for the restrictions contained in Article 104 of the law, they indicate that social media on the network is not exempt from obtaining the necessary license in accordance with other effective laws, and that the council may require obtaining a license as a condition for accrediting these means. At the same time, the article allows the competent public entities to set additional conditions for accrediting social media outlets that provide content related to the nature of those entities’ work.

With all these restrictions on granting licenses, the executive instructions of the law themselves added more, when they interpreted Article 6 regarding obligating media outlets to allocate no less than 5% of their total annual advertising space for public benefit advertisements free of charge, such as environmental, public health, cultural advertisements, and those for civil society organizations, and others.[32]

Even though the National Media Council was of a shapeless character emptied of the practical content of a body supposed to organize media work with complete independence, Assad’s regime issued Legislative Decree No. 23 of 2016, by which it abolished the provisions of Chapter IV of the Media Law issued by Legislative Decree No. 108 of 2011, i.e., abolishing the National Media Council and transferring all duties and powers that the council had to the Ministry of Information.[33] Accordingly, it is not legally consistent to transfer duties and powers that were granted to a body considered an independent authority with legal personality, whose goal was to regulate media work that is supposed to be independent and free, to another body of the executive authorities even if it is the Ministry of Information, which naturally expresses the opinion and agendas of the authorities!

B. Law No. 19 of 2024

In the year 2024, the Assad regime issued Law No. 19 providing for the establishment of the Ministry of Information, to replace the ministry established by Legislative Decree No. 186 of 1961 with its rights and obligations. The law consists of 18 articles, through which it expanded the powers of the Ministry of Information and enabled it with oversight tools in addition to what was the case in previous similar laws.[34]

The law, through its texts, clearly violates freedom of the media and opinion and expression, and has become a new means to control the work of journalists, control media content, and exercise more oversight over the private press and printed materials that enter the country, as well as imposing more restrictions on the drama industry.[35]

Article 4 of the law specified the tasks of the Ministry of Information with broad powers that entrench state control over the media sector, and subject the various aspects of journalistic and media work to direct supervision by the executive authority. The law granted it the authority to set regulations for organizing the media sector and investment in it, to communicate with foreign media in order to convey state policies to external public opinion, to coordinate with international organizations for training media cadres, in addition to undertaking research, studies, and opinion polls, supervising the advertising industry, organizing the distribution of printed materials, reviewing drama content and organizing its production, as well as regulating the work of foreign correspondents, monitoring printed materials entering Syria, monopolizing the representation of Syrian media and drama abroad, and granting licenses to publishing houses and media service companies.

Articles 8 and 9 of the law also stipulated the formation of the “National Drama Committee,” empowered to set policies for drama production, review its texts, and determine mechanisms for its export.

It is noted that these powers also extend to withdrawing functions that were granted to existing professional institutions such as the Syrian Journalists’ Union, as Article 12 stipulated the transfer of the power to grant documents proving media status from the Union to the Ministry of Information, which reflects a clear orientation towards centralizing media decision-making and subjecting it to direct governmental oversight, at the expense of the independence of the profession and its professional unions.

C. Cybercrime Law No. 20 of 2022

In 2022, the Assad regime issued the Cybercrime Law to reorganize the penal legal rules of cybercrime contained in Legislative Decree No. 17 of 2012. Law 20 consists of seven chapters distributed over 50 articles.[36]

Continuing the previous approach of imposing complete domination over the media and preventing any manifestation of independent media, the Assad regime government adopted systematic policies based on restriction and blocking, parallel to the policy of silencing practiced in the internal sphere. Documentation showed the blocking of 161 websites in Syria up to April 28, 2008, including prominent sites such as “YouTube,” in clear indication of the comprehensive nature of this repressive policy towards the digital space. (Taming the Internet, Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, 2008).

Law 20 abolished Decree 17 of 2012, and defined information, network and software, application, website, digital content, service providers, privacy, traffic data, and other definitions, some of which were mentioned in another law such as Media Law 108.

The law expanded the scope of cybercrime beyond what was in the repealed Decree 17. It defined it as: “A criminalized conduct according to the provisions of this law committed by means of information technology, targeting information or information systems, or related to adding digital content on the network.” Whereas the repealed Decree 17 defined it as: “A crime committed using computer devices or the network, or occurring on information systems or the network.” That is, Law 20 considered that digital content added on the network is considered a crime if it violates the provisions of the law. Accordingly, content related to freedom of opinion and expression, and even publishing correct information (such as publishing the real value of the Syrian currency against foreign currencies), can be considered a crime according to the same law.[37]

Law 20 added new types of crimes covered by its provisions, which undermine the work of journalists and media outlets and restrict freedom of opinion and expression. Article 27 stipulated that: “Anyone who created or managed a website or an electronic page or published digital content on the network with the intent to provoke acts aimed at or calling for changing the constitution by illegal means, or detaching part of Syrian territory from the sovereignty of the state, or provoking armed rebellion against the authorities existing by the constitution or preventing them from exercising their functions derived from the constitution, or overthrowing or changing the system of government in the state…” Likewise, Article 28 when it stipulated that: “Anyone who by one of the means of information technology publishes false news on the network that would undermine the prestige of the state or harm national unity…” and Article 29 which stipulated that: “Anyone who created or managed a website or an electronic page or published digital content on the network with the intent to cause depreciation or instability or to undermine confidence in the national currency or its exchange rates set in the official bulletins…” and other legal texts which in the context of the law took a strict orientation regarding type of punishment and fines.

And as we mentioned in the framework of analyzing the provisions of Media Law 108 of 2011, the Assad regime used similar terms as in previous laws, through using vague terms that the regime and the security services could interpret in the manner they see fit in the framework of disseminating and circulating information and news as well.

With such vague texts and terms open to multiple interpretations, anyone publishing in the electronic space, whether individuals or institutions, can be punished, and they allow the security services to pursue and arrest them. This approach in interpreting the texts of Law 20 was also followed by its executive instructions.[38]

D. Syrian Penal Code (provisions related to freedom of expression, publication, and media work)

The Syrian Penal Code No. 148 of 1949 and its amendments does not differ from other laws in terms of its general approach to dealing with the issue of freedom of opinion and expression and regulating some media practices. Although it constitutes the general framework that organizes the basic rules related to freedom of opinion and expression and the practice of media work in Syria, it was limited to some specific legal texts.

Article 285 of the Penal Code stipulates: “Whoever in time of war or when expecting its outbreak engages in propaganda aiming to weaken national sentiment or to awaken racial or sectarian strife shall be punished with temporary imprisonment.”

2Article 286 stipulates: “He shall be punished by imprisonment for one to three years any Syrian who published abroad, or helped in publishing false or exaggerated news that would undermine the prestige of the state or its financial standing.”

Article 287 stipulates: “Whoever in Syria, in cases other than those stated in the previous article, publishes false or exaggerated news that would weaken the morale of the nation shall be punished by imprisonment for six months to three years.”

Some of these vague terms were also mentioned in the Media Law and other laws regulating media practices. All previous laws, including the Penal Code, agreed in their general approach of lacking a criterion and standard for interpreting them. There is no clear criterion for interpreting what is meant by undermining the prestige of the state, or weakening national sentiment, or weakening the morale of the nation. Rather, Assad’s regime used these terms, as we explained in the discussion of Media Law 108, to repress freedoms and silence voices, including ideologizing media according to its policies. The regime’s security services went further by killing and pursuing journalists and anyone working in the media sector if they strayed outside the regime’s official narrative.

E. Media Law in Areas Controlled by the Democratic Union Party (PYD)

The Autonomous Administration affiliated with the Democratic Union Party (PYD) announced in 2015 the first Media Law, composed of 33 legal articles regulating media work inside its areas of control, until a new Media Law was adopted in all of Northeastern Syria in 2021, followed by the issuance of an executive bylaw for the law supervised by the Media Department in the Autonomous Administration.

The law issued in 2021 contains articles restricting media freedoms, the most prominent of which are those contained in the executive bylaw of the law with provisions granting the “Media Department” the authority to “withdraw the work license directly from any media institution or journalist if its work is hostile to the values and sanctities of the people and institutions in North and East Syria,” without precise definition of the concept of “values and sanctities,” which opens the way to arbitrary interpretations according to what the authorities there see.

Also, the texts that prevent the journalist from addressing the private life of officials or public figures, without distinguishing between personal conduct and functional conduct, contradict principles of transparency and public accountability. The problem increases when judicial authorities are authorized, according to the law, the right to demand from the journalist disclosure of his sources of information in some cases, which represents a violation of international standards that consider protecting sources of information as one of the basic pillars of press freedom. In addition, the Media Department affiliated with the Autonomous Administration monopolizes comprehensive powers without actual guarantees of oversight or accountability, which undermines the principle of self-regulation of journalists and press freedom.

It is notable that the executive bylaw of the law created some provisions not mentioned in the law, where the law imposed disciplinary and financial penalties on journalists and institutions, including suspending the journalist from work, and imposing financial fines starting from 100 US dollars and reaching 500 US dollars, while the fine imposed on media institutions may reach 1000 US dollars, according to what was mentioned in the articles related to violations and media discipline in the executive bylaw.[39]

Areas of the Autonomous Administration have witnessed continuous decline in press freedoms since the issuance of the Media Law in May 2021, where many media institutions were closed, others were banned from working, and violations against journalists continue, especially those working in independent media outlets. In February 2024, restrictions against press freedoms escalated, by imposing the provision of information about workers in media outlets to the Autonomous Administration, and the Media Department is accused of restricting through procrastination in renewing licenses, imposing red lines that expose journalists to prosecution, and granting permits only to parties that align with the political orientation of the Administration.[40]

F. International Standards Related to Media Freedom

International standards of media freedom constitute the basis upon which democratic states build their media systems, and they are a legal and ethical reference guaranteeing the protection of freedom of expression, strengthening the independence of media outlets, and protecting journalists from violations and restrictions. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) is considered the cornerstone in this framework, as it stipulates that: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”[41]

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), which the Syrian Arab Republic acceded to by Law No. 25 of 1969, also enshrined this right in Article 19 as well, but added a binding legal dimension for State parties, as it stipulated that: “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.” The Covenant also indicated that any restrictions imposed on this right must be necessary, prescribed by law, and aimed at achieving a legitimate interest such as respect for the rights of others or protection of national security and public order.

Other documents and reference frameworks of guiding or consensual nature reinforce these principles, such as:

● The Windhoek Declaration (1991) issued by UNESCO, which emphasized the importance of independence and plurality of media outlets, especially in countries emerging from conflicts or undergoing political transition.[42]

● The Johannesburg Principles (1995), which provide precise guidance on balancing freedom of expression with the requirements of national security, and affirm that restrictions must be narrow in scope, subject to judicial review, and not arbitrary.

● The Munich Declaration of Journalism Ethics (1971), which identified ten professional principles governing journalistic work, foremost of which are respect for truth and the public’s right to knowledge, rejection of distortion, non-discrimination, and respect for individuals’ privacy.[43]

Alongside these documents, international organizations such as Reporters Without Borders, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), and the International Federation of Journalists are active in monitoring the extent to which states respect media freedom, and they issue periodic reports used as indicators to evaluate the media environment and the level of freedoms therein.[44]

In the Syrian context, these standards are considered vital evaluation tools, given the weakness of national legal frameworks and the absence of effective guarantees for media independence and the safety of journalists. The laws in force in different areas of control often contradict these principles, whether by imposing censorship, restricting plurality, limiting access to information, or criminalizing critical expression.

The importance of these international standards in the Syrian case appears as a reference to identify the gap between the desired and the actual reality, and to formulate recommendations based on globally recognized standards in order to enhance media freedom, protect journalists, and develop the legal structure in line with Syria’s obligations as a member of the United Nations, even if it is not actually committed to those principles.

In general, the legal texts in Syrian laws contradict the principle of legality which requires that penal texts be clear, precise, and not subject to interpretation, as stated in Article 15 of the Covenant.

They also do not comply with Article 19 of the same Covenant, nor with General Comment No. 34 issued by the Human Rights Committee, which emphasizes that restrictions on freedom of expression must be “clearly defined,” “necessary,” and “proportionate.”[45]

Likewise, the independence of media regulatory bodies from the executive and legislative authorities is a basic condition to guarantee a free and pluralistic media environment. This was affirmed by international principles regulating freedom of expression and media broadcasting. From a legal point of view, these bodies should not be subject to direct subordination to any governmental body or political interests, because that poses a direct threat to their neutrality and credibility. This was explicitly stated in the “International Principles for Media Legislation” issued by ARTICLE 19, which stress that regulatory bodies should be established by clear laws, and that their powers should be granted within a framework of transparency and accountability, away from political or governmental influences.[46]

A study titled Broadcasting, Voice, and Accountability issued by the University of Michigan Press in cooperation with the World Bank pointed out that one of the basic pillars of organizing the media sector in a democratic way is the establishment of independent bodies that regulate and monitor media performance, and are granted clear powers to ensure compliance with professional standards without interference from the government or political actors.[47]

Any breach of this rule constitutes a violation of the public’s right to free and pluralistic media, and empties the principle of self-regulation of its content, and contradicts states’ obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, especially Article 19 thereof.

It becomes clear from analyzing the legal framework regulating media work in Syria, whether under successive governments or de facto authorities, that there is a deep gap between these legislations and the international standards that guarantee media freedom and protect journalists. The prevailing legal environment is characterized by ambiguity, restriction, multiple references, and prioritization of the security aspect over the rights aspect. This produced a fragile media reality, where freedom of expression is under constant pressure, and media work is practiced in the absence of legal guarantees and independence.

In contrast, international standards provide an integrated system that guarantees media freedom as an inherent right that cannot be restricted except in the narrowest limits and under clear and justified conditions, making them an indispensable reference for any legal reform process aiming to build free and responsible media.

The sharp disparity between local legal texts and international standards requires a comprehensive review of the legislative system related to media in Syria, to ensure harmonization with international human rights obligations, and to establish a legal environment that supports media independence, protects journalists, and entrenches the principle of accountability instead of punishment.

G. Importance of Freedom of Forming Unions, Supporting Them, and Guaranteeing Their Independence

Press unions play a pivotal role in protecting media freedom, defending journalists’ rights, and enhancing professional practice. Independent unions are considered one of the basic guarantees of a free and pluralistic media environment.

International standards affirm that the right to freely establish and join unions is an inseparable part of basic human rights. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights stipulated in Article 22 that: “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of his interests.” The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights enshrined this right in Article 8 as well, emphasizing the freedom of unions to operate without interference from authorities.[48]

In the same context, ILO Convention No. 87 of 1948 concerning “Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize” [49]is the basic reference to guarantee the independence of unions. It affirms the right of workers, including journalists, to establish their organizations freely without state interference, and to manage their affairs and organize their activities and set their internal rules freely. The convention explicitly states that public authorities must refrain from any interference that would restrict this right or hinder its lawful exercise.

In Syria, the union reality remained subject to state domination for decades, especially under the rule of the Ba’ath Party and the Assad regime, which linked union work with political leadership. This was reflected in the Syrian Journalists’ Union, which acts as an institution practically affiliated with the executive authority, without organizational independence or real representation of journalistic will. Current Syrian laws, including the Trade Union Law, prohibit any attempts to establish alternative or independent unions, which makes it difficult for journalists to express their interests freely or defend themselves against violations and pressures.

With the development of the media scene and the multiplicity of ruling authorities in Syria after 2011, alternative professional initiatives emerged in some areas, most notably the Syrian Journalists’ Association, established in 2012 as an independent initiative outside the official authority framework. However, these initiatives still lack legal recognition inside Syria, which places them in a state of legal fragility and limits their ability to directly influence policy-making or defend journalists within the national system.

The absence of a modern law guaranteeing freedom of union organization, and the continued subordination of press unions to official institutions, constitutes one of the main obstacles to developing a free and independent media environment in Syria. Therefore, there is a need for comprehensive legislative reform guaranteeing journalists their right to free union organization in accordance with international standards, including the enactment of a new union law recognizing the right to union plurality, prohibiting authorities from interfering in their affairs, and enshrining their financial and administrative independence.

This step is essential to guarantee the protection of journalists, strengthen their ability for collective bargaining, and contribute to shaping media policies from the position of partner, not subordinate. It must be an essential part of any political or legal reform process in Syria’s future.

H. Foundational References for Media Freedom in Syria: From the Demands of the Revolution to Constitutional Guarantees

To ensure free media in Syria, three axes are needed: a philosophical reference and convictions that are principles adopted by society, the state, and the judiciary, and form the basis for laws; a constitutional and legal reference that guarantees freedom of expression; and an independent judiciary that guarantees the interpretation and application of media freedom laws.

First: The Philosophical Reference

The Syrian revolution which erupted in March 2011 constituted one of the most prominent milestones of popular mobilization in the Arab world. Its central demands were summarized in freedom, dignity, and ending authoritarianism. The revolution came as an extension of the wave of the “Arab Spring,” but it carried a Syrian specificity in terms of the structure of the regime, the complexity of the social and political composition, and the speed of the militarization of the conflict. In this context, the concept of freedom emerges as a central principle forming the core of the revolutionary discourse, and a main determinant of Syrians’ aspirations in rebuilding their state and society.